California students did better than ever on the state’s achievement tests. More of them scored at the proficient level or above in math and English than at any time since the testing program began in 2003. But the pace of change may put a twist on the fabled lesson of slow and steady wins the race.

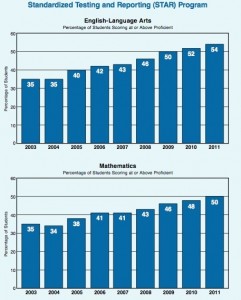

Of about 4.7 million students in grades 2 through 11 who took the California Standards Tests (CST) last spring, 54 percent were proficient or better in English language arts (ELA) and 50 percent scored proficient or higher in math – an increase of 19 percentage points in ELA and 15 percentage points in math over nine years.

In announcing the results on Monday, State Superintendent of Public Instruction Tom Torlakson credited the increases to the “heroic efforts of teachers” and “valiant work of administrators, classified school employees, and parents” despite the billions in cuts to education in recent years, and wondered aloud how well students might do if schools were funded at a decent level.

Slow and steady progress not enough

Here’s the part, however, where the seemingly large increases of 19 and 15 points begin to shrink. On a yearly basis, that amounts to barely 2 percentage points.

“You have to ask yourself is that enough?” said Ron Dietel, with the National Center for Research on Evaluation, Standards, & Student Testing (CRESST) at UCLA. “They wouldn’t cause me to jump up and down and say it’s anything more than teaching the curriculum.”

What’s more, said Dietel, if you look at the state’s scores on the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), a standardized test taken by a large sample of fourth and eighth grade students across the country, California students score below the national average of proficient or better in math and English for both grades.

While NAEP isn’t aligned to California’s standards, Dietel said it’s still the “closest thing to having an outside barometer in terms of how states are performing.”

Two percent a year also doesn’t impress James Lanich, director of policy and research for California Business for Education Excellence, who says he’s not surprised by the results. “We basically have no functional accountability system,” said Lanich, explaining why there are no incentives for schools to try harder.

“I have a litmus test; I ask the question, ‘What happens to a school or a school district that is not doing its job?’ And the answer is ‘absolutely nothing.’ And I’ll ask the reverse question; ‘What happens to a school that’s doing an extraordinary job?’ And the answer is ‘absolutely nothing.'”

Minding the gap

Still, Lanich sees many examples of the “valiant” efforts that Torlakson described, particularly when it comes to closing the achievement gap.

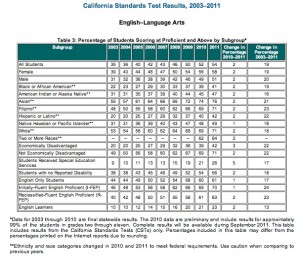

Statewide, the gap has been with us for so long it seems immutable. While 76 percent of Asian students and 71 percent of white students score at proficient or above in ELA, just 41 percent of African American students and 42 percent of Hispanic students reach those levels. Corresponding results in math are lower for every subgroup, with the exception of Asian students.

But some districts are making progress in bringing everyone closer together. Hispanic students in Santa Clara County reduced the achievement gap with white students from 43 percentage points to 38 in ELA, and from 39 to 30 in math for students in second through seventh grades.

“The important point to make,” said Charles Weis, Superintendent of the County Office of Education, is that “it didn’t happen because top performers came down; every group continued to go up this year and the Hispanic group grew even faster.”

Statewide, students showing the greatest one-year gains are those receiving special education services. While the number scoring proficient or above in math fell within the statistically expected 3 percentage points, in English language arts they jumped by five points from 2010 to 2011.

But even that may not be what it appears. As John Fensterwald reports today in the Educated Guess, the increase may have more to do with who isn’t taking the CST than who is taking it.

There are also signs the state is coming to terms with another gap of sorts: the subject gap. Ever since high stakes testing began, critics have worried that anything not math or English was getting short shrift. It’s not just a California thing. On the most recent NAEP history exam, 17 percent of eighth grade students performed at or above proficient, meaning more than 80 percent couldn’t explain changes in colonial slave practices or identify the rights protected by the first amendment.

So it seems noteworthy that more California students are taking the standardized tests in science and history and they’re scores are improving, albeit as slowly as in math and English.

Despite all the “buts,” it’s understandable that superintendents and principals are pleased – or at least relieved – by the results. They show success in efforts to keep budget cuts as far away from the classroom as possible. But – there’s that nagging word again – that margin of protection may not hold if districts are hit with mid-year cuts.

“That really is the big question right now,” said Santa Clara County Superintendent Charles Weis. “If we keep starving the system it’s inevitable that we’re going to see a dip, and I’m just very pleased that we didn’t see it this year.”