Julio is not looking forward to his 19th birthday. On that day in December, he’ll lose his apartment, his living expenses, and the support of the state’s foster care system. One month later, in January 2013, the young Modesto man will be eligible to reapply for foster services under AB 12, the California Fostering Connections to Success Act of 2010.

Four weeks may not seem like a long time, but for Julio – who doesn’t want his last name used – it couldn’t come at a worse time. Next December he’ll be taking finals at Modesto Junior College, on the way to earning a four-year degree at Cal State Stanislaus, and he says the pending disruption in his life is scary.

“During that time I wouldn’t know where I would be and where I would get my money from; I would be pretty much homeless unless I found somewhere to live,” said Julio. “You wouldn’t have a place to stay even during finals, which is the most stressful time of the year; you would have to move at that time.”

Julio is one of the so-called foster care “bubble” youth. These are young adults who fall into an unintended consequence of AB 12. That bill, by Assemblyman Jim Beall (D-San José), allows foster youth to remain in the system until they turn 20 (possibly 21 if the Legislature funds it). But in order to win the signature of former Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger, Beall had to agree to phase in the change over three years.

- Effective January 1, 2012, extends foster care to eligible youth up to their 19th birthday;

- Effective January 1, 2013, extends foster care to eligible youth up to their 20th birthday; and

- Effective January 1, 2014, extends foster care to eligible youth up to their 21st birthday.

The way the legislation is written, young adults who turn 19 between January 1, 2012 and December 31, 2012 must leave the foster care system. They can reapply on January 1, 2013, and then go through the same thing again when they turn 20.

So this year Beall introduced AB 1712 to patch up the holes in his original legislation and provide continuous coverage up to age 21. It’s actually the second cleanup bill; last year, the Legislature passed AB 212, which established the process for implementing the age changes.

“It’s a fundamental shift in the whole mentality of the foster care system,” Beall explained. “You think any 20-year-old kid with limited education can find a job now? I don’t. The idea is to get them positioned to go into vocational training or get into college and get a degree.”

Advocates and many juvenile court judges agree. Beall’s legislation is supported by the California Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, California Coalition for Youth, and the California State Association of Counties.

Los Angeles County has been permitting foster youth to stay beyond age 18 for several years now, said Harvey Kawasaki, Division Chief of Youth Development Services. Even before AB 12, courts there routinely allowed young adults in foster care to stay in the system, and Kawasaki says a little over 78 percent, or 212 emancipated foster youth, decided to stay in the program. That’s a little more than the County expected.

“To me, it really is based upon what the youth wants to do and the ability of the youth along with their social worker to develop a plan and have concrete things in place,” said Kawasaki. “I get concerned when I hear, ‘Oh, I’m going to live with my friends.’”

Los Angeles County is one of a handful that does this willingly and on its own. The others are San Francisco, Alameda, Santa Clara, and San Mateo. The group Fostering Media Connections, along with UC Berkeley’s Center for Social Services Research, created an interactive map showing where the counties stand.

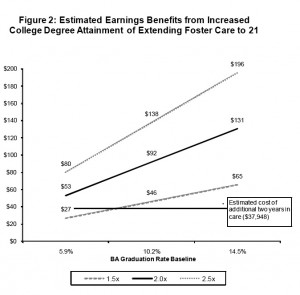

During the gap period, Los Angeles County picks up the tab, which Kawasaki said varies depending on each foster youth’s circumstances and needs. In Modesto, Julio receives $776 a month for living expenses, including rent and food. A study on the costs and benefits of AB 12 estimates the annual price of extending foster care cost through 21 at approximately $37,948 per person. Of that, the federal government contributes $13,282 and counties pay $14,800.

But the researchers say the benefits far outweigh the costs in higher rates of college going, fewer high school dropouts, fewer teen pregnancies, better job training, and fewer people on public assistance or in prison. The study’s authors estimate that allowing young adults to remain in foster care until they’re 21 in order to attend college or vocational school increases their work-life earnings by $84,000.

AB 1712 is scheduled to come before the Assembly Appropriations Committee tomorrow. Today, several dozen foster youth are holding a rally in support of the measure at the State Capitol. Assemblyman Beall believes the committee will pass it. When asked why he’s so optimistic given the state’s fiscal troubles, he responded, “Because that’s the right thing to do. If you don’t do it, what does that say?”

To learn more:

- California Alliance of Child and Family Services

- California Dept. of Social Services, Children and Family Services Division

- California Youth Connection

- California’s Fostering Connections to Success Act and the Costs and Benefits of Extending Foster Care to 21

- Fostering Media Connections

- John Burton Foundation