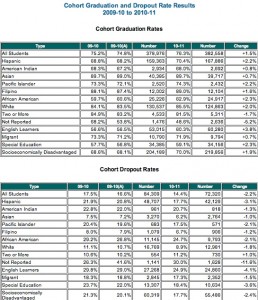

California’s high school graduation rate is edging upwards for most groups of students. The overall graduation rate for 2010-11 was 76.3 percent, or 1.5 percent above the prior year.

Tom Torlakson, the State Superintendent of Public Instruction, acknowledged that while it’s not a surge, it’s still good news.

“It’s heading in the right direction; it’s certainly not where we want it to be,” said Torlakson during a telephone conference call with journalists on Wednesday. “The thing that I think is more noteworthy is the larger gains we’re seeing among Hispanics and African American students.”

The graduation rate for Hispanic students increased by 2.2 percent to 70.4 percent, and rose by 2.3 percent among African American students to reach 62.9 percent. At the same time, dropout rates for those groups of students fell by 3.1 percent and 2.1 percent respectively. English learners also showed progress, with a 3.8 percent increase in their graduation rates.

Torlakson said these improvements are especially striking because they’re happening “in the face of terrible budgets, a lot of turmoil and uncertainty in schools, more crowded classrooms, a shorter school year, summer school being eliminated,” and a shortage of textbooks, computers, and science lab equipment.

He credited the change to more focused interventions for low-income students at risk of dropping out, such as AVID and the Puente Project, that give them the support, encouragement, and college prep skills to put college within their grasp.

The CALPADS difference

This is the second year that the state has calculated graduation and dropout rates using CALPADS, the longitudinal student data system that uses unique student identifiers.

With CALPADS, state education officials can track student progress from ninth grade to twelfth grade, accounting, for the most part, for students who transfer to other public schools in the state, earn GEDs, and even those who stay in high school for a fifth year to graduate.

“This is the first time we’ve been able to compare the rates from one year to the next, and for them to be used in the federal accountability system,” said Keric Ashley, director of the data management division at the state department of education. Starting next year, Ashley said California will have enough data to calculate graduation and dropout rates for students starting in seventh grade.

Nearly all states now use a similar system required by the federal government for reporting under the Elementary and Secondary Education Act. Before CALPADS, there was little consistency, and not always great accuracy, in how districts and the state computed these rates. One common approach was to take a head-count of students in ninth grade and subtract the number remaining at the end of twelfth grade. Another method was to add up all the 17-year-olds reported to be in public and private schools and divide that by the total population of 17-year-olds.

Even CALPADS has limitations and some bugs to be worked out. As the chart on the left shows, there are two columns for the class of 2009-10 – the first is 09-10 and the second is 09-10(A). The “A” stands for adjusted. Ashley explained that when CDE was reviewing the rates for the class of 2011, they noticed that some graduates had been in high school for more than four years so they were actually part of the previous year’s cohort and had to be switched. There will be another adjustment in December, when school districts will have another opportunity to make corrections to their data.

CALPADS also doesn’t know if a student transfers to a private high school in California, switches to home schooling or leaves the state unless the original school gets documentation from the student’s family and sends it to the state department of education. It also doesn’t track students who complete high school in different venues, such as an adult education program at a community college.

These are small gaps and won’t account for big changes in the numbers, but having more and better data can be meaningful, said Russell Rumberger, director of the California Dropout Research Project at UC Santa Barbara and author of the book Dropping Out: Why students drop out of high school and what can be done about it.

“We’d like to know how many of our students eventually graduate and go on to college,” said Rumberger. ”As a state we’d like to know everybody who completes, however and whenever they do it.”