In a decision with statewide implications, a Superior Court judge ruled that Los Angeles Unified must include measures of student progress, including scores on state standardized tests, when evaluating teachers and principals.

But Los Angeles County Superior Court Judge James Chalfant will leave it to the district, in negotiations with its teachers union and administrators union, to determine what other measures of student performance might also be included, how much weight to give them in an evaluation, and how exactly test scores and other measures should be used.

Chalfant’s decision would appear to strengthen Superintendent John Deasy’s push to move forward with a complex value-added system of measuring individual students’ progress on state standardized tests, called Academic Growth over Time. Deasy wants to introduce AGT on a test basis in a pilot evaluation program next year. But the unions remain adamantly opposed to AGT; Chalfant said the use of AGT as a measure of student progress is not his call to make; and today, hours before Chalfant is to meet again with parties in the lawsuit over evaluations, Los Angeles Unified school board member Steve Zimmer will propose barring AGT from staff evaluations. The school board will vote on his motion later this month.

Chalfant released his tentative decision on Monday. (Update: On Tuesday, after a hearing with all parties, he made the ruling final.) But the carefully crafted, 25-page ruling is not likely to change much, if at all, and may become final today, after the school district and unions get a final chance to make their case at a hearing.

The ruling is a victory for Sacramento-based EdVoice, which filed suit on behalf of a half-dozen unnamed Los Angeles Unified students and their parents and guardians. EdVoice’s lawsuit claimed that the Stull Act, the 40-year-old state law laying out procedures for teacher and administrator evaluations, requires school districts to factor in student progress on district standards, however they decide to measure it, as well as scores on the California Standards Tests (CST) in evaluations and that Los Angeles Unified was ignoring the requirement – as do most school districts.

Chalfant agreed and, in his decision, quoted Deasy, who, in testimony, acknowledged the district doesn’t look at how students do academically when evaluating teachers. On Monday, Deasy praised the tentative decision, and called for the district, his employer, to move quickly to act on it. “The district has waited far too long to comply with the law,” Deasy said. “This is why LAUSD has created its own evaluation system, and has begun to use it. The system was developed with the input of teachers and administrators.”

Next step: negotiating compliance

Chalfant’s tentative ruling proposed that attorneys for EdVoice and the parents propose a plan for compliance and that they and the district try to negotiate specifics over the next month. Whatever they agree to would still likely have to be negotiated with United Teachers Los Angeles and Associated Administrators Los Angeles.

Bill Lucia, president and CEO of EdVoice, praised Chalfant’s decision. While acknowledging that the emphasis given to student progress could become a sticking point in negotiations between the district and teachers, he said the ruling makes clear “there is no status quo going forward.”

“It won’t be OK to sit on their hands,” Lucia said. “The district must come up with something different that passes the laugh test and makes a sincere effort to honor the statute requiring that evaluations look at whether kids are learning.”

EdVoice took no position on whether the AGT should be the tool by which to measure student performance in Los Angeles. But, Lucia said, the district must consider other measures – whether student portfolios or other district tests – in the evaluations of teachers of courses in which CSTs aren’t given, such as first grade, art and seventh grade science.

Signal to other districts

Chalfant’s ruling would apply only to Los Angeles Unified, although other Superior Courts could cite the ruling. Nonetheless, Lucia said that the message to other districts is that “a district cannot omit the progress of kids in job performance of adults.” The goal, he said, “should be a better determination of effectiveness that allows limited resources to be targeted to those teachers needing the most improvement.”

Attorneys for UTLA and the district could not be reached for comment on Monday.

UTLA argued in its brief that a dispute over requirements in the Stull Act belonged before the Public Employee Relations Board, not a court, and that any requirement for the use of test scores or other measures must be negotiated. But Chalfant wrote that first and foremost, the district must comply with state law, regardless of the contract it reached with the unions.

The position of the district, on behalf of the school board, was confusing. Last year, in defending the pilot program using AGT, the district said it had the authority to impose the terms of evaluations without union negotiations. Even though Deasy testified that test scores and student progress weren’t part of staff evaluations, the district fought the EdVoice lawsuit.

In its brief, the district asserted that the use of AGT in the pilot satisfied the law’s requirement to use state standardized test scores – even though they have yet to be applied, with consequences, to any teacher. The district also asserted that it uses results on district and state tests and other student measures to set goals for teacher instruction and measure improvements in the classroom.

But Chalfant ruled that that’s not sufficient. “There must be a nexus between pupil progress and the evaluations. No such nexus currently exists.”

“This does not mean that there must be a box on a form which directly addresses pupil progress,” he wrote. “It does mean that pupil progress must be reflected in some factor on a written teacher evaluation.”

Whether pupil progress – AGT alone or in combination with other student growth measures – counts 20 percent or 30 percent of an evaluation, as Deasy has advocated, must be decided through negotiations, unless the district asserts a right to impose AGT unilaterally.

Villaraigosa’s Stull Act amendment

In 1999, when he was state Assembly speaker, Los Angeles Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa sponsored an amendment updating the Stull Act to require the use of CST scores in teacher evaluations. Villaraigosa submitted a brief supporting this position.

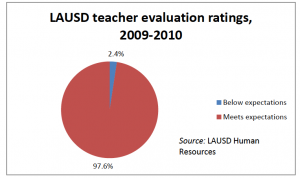

Chalfant incorporated some of Villaraigosa’s points in explaining the rationale for his decision. In 2009-10, 99.3 percent of teachers evaluated received the highest evaluation rating, with 79 percent meeting all 27 measures of performance. This despite that the district “has one of the lowest high school graduation rates in the State, and an even lower percentage of students are college ready.”

“These failures cannot be laid solely at the feet of the District’s teachers,” Chalfant cointinued. “Students must want to learn in order to do so, and some students can never be motivated to learn. But the District has an obligation to look at any and all means available to help improve the dismal results of its student population. One means of improving student education is to evaluate teachers and administrators based on the overall progress of their students.”