With teachers and organized labor rallying against what they called an unnecessary attack on their rights, a bill that would make it easier to fire teachers and administrators accused of serious sexual and violent offenses against children failed to pass the Assembly Education Committee on Wednesday. Sen. Alex Padilla’s controversial SB 1530 will be dead for the session unless he can persuade one more Democrat to reverse positions within the next week .

The bill had bipartisan support in the Senate, where it passed 33-4, but, in a test of strength by the California Teachers Association, only one Democrat, Education Committee Chairwoman Julia Brownley, and all four Republicans backed it in the crucial committee vote. The other six Democrats either voted buy clomid online against it (Tom Ammiano, San Francisco; Joan Buchanan, San Ramon) or didn’t vote (Betsy Butler, El Segundo; Wilmer Carter, Rialto; Mike Eng, Alhambra; and Das Williams, Santa Barbara).

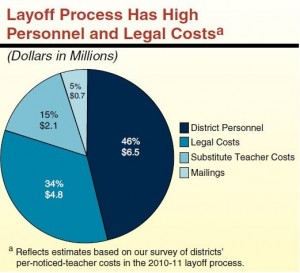

The bill follows shocking incidents of sexual abuse in Los Angeles Unified and elsewhere, the worst of which involved Mark Berndt, 61, who’s been accused of 23 lewd acts against children at Miramonte Elementary in LAUSD. Padilla, a Democrat from Van Nuys, said SB 1530 responded to complaints from superintendents and school board members that it takes too long and is too expensive to fire teachers facing even the worst of charges. Rather than go through hearings and potential appeals, LAUSD paid Berndt $40,000, including legal fees, to drop the appeal of his firing.

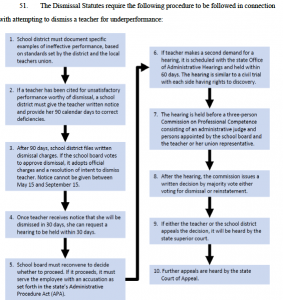

Under current law, dismissal cases against teachers and administrators go before a three-person Commission on Professional Competence, which includes two teachers and buy amoxil online an administrative law judge. Its decision can be appealed in Superior Court.

Narrow band of ‘egregious’ cases

SB 1530 would have carved out a narrow band of exceptions applying to “egregious or serious” offenses by teachers and administrators involving drugs, sex, and violence against children. In those cases, the competence commission would be replaced by a hearing before an administrative law judge whose strictly advisory recommendation would go to the local school board for a final decision, appealable in court.

The bill also would have made admissible evidence of misconduct older than four years. Berndt had prior reports of abuse that had been removed from his file, because a statute of limitations in the teachers contract in LAUSD prohibited their use.

School boards already have final say over dismissal of school employees other than teachers and administrators, so the bill would extend that to efforts to remove “a very creepy teacher” from the classroom,” as Oakley Union Elementary School District Superintendent Richard Rogers put it. “What is more fundamental than locally elected officials responsible for hiring and dismissal?” he asked.

The bill has the support of the administrators and school boards associations, Los Angeles Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa, and the LAUSD president, Monica Garcia, who described her fellow board members as “seven union-friendly Democrats” who want to “get rid of people who will hurt our children.”

Current law works

But Warren Fletcher, president of United Teachers Los Angeles, countered that “SB 1530 solves nothing, places teachers at unfair risk, and diverts attention from the real accountability issues at LAUSD.” Turning the tables, Fletcher, CTA President Dean Vogel, and others have filed statements with the state Commission on Teacher Credentialing to investigate Superintendent John Deasy’s handling of misconduct allegations in the district.

The argument that current law works resonated with Buchanan, who served two decades on the San Ramon Valley School Board. Calling the bill “intellectually dishonest” because nothing can prevent another Miramonte from happening, she said, “We never had problems dismissing employees.” She acknowledged that the “long, expensive dismissal process” needs to be streamlined, but the bill doesn’t get it right. A teacher at a school in her legislative district was accused of sexual misconduct by a student who got a bad grade. That teacher “deserves due process.”

The two teachers on the Commission on Professional Competence provide professional judgment that’s needed to protect the rights of employees, said Patricia Rucker, a CTA lobbyist who’s also a State Board of Education member. “We do value the right to participate and adjudicate standards for holding teachers accountable,” she said.

Fletcher said that school boards would be subject to parental pressure in emotionally charged cases, and, as a policy body, should not be given judicial power. Assemblyman Ammiano, a former teacher, agreed. “A school board is not the one to make the decision,” he said.

Julia Brownley said that she too was concerned about false charges against teachers but would support the bill, for it “will give districts tools” for rare circumstances. The bill would make the dismissal process more efficient and definitive. And she agreed with Padilla that the bill ensured due process for teachers, who’d be allowed to present their case, with witnesses, before an administrative judge and appeal an adverse decision to Superior Court.

Oakley Superintendent Richards said that the CTA misstated what SB 1530 does and “has taken such an extreme position on this issue that they have lost credibility.” The union’s real fear is that the bill will be “a nose under the camel’s tent” to change the dismissal process for all teachers. And that, he said, is unfounded.

Padilla was to have issued a statement last night on the setback in the committee but didn’t. Update: Padilla issued a statement this morning that reads, in part: “SB 1530 was narrowly crafted to focus only on cases in which school employees are accused of sex, violence, or drug use with children. It is difficult to understand why anyone would oppose a measure to protect children. It is very disappointing.”